The Triple Jeopardy of Attention

Reprising their packed session at Cannes this summer, System1’s Orlando Wood joined Amplified Intelligence CEO Karen Nelson-Field and effectiveness expert Peter Field to discuss The Triple Jeopardy Of Attention. Three interlocking threats to effectiveness with one common root – undervaluing attention as a metric and goal for advertising.

The full session is fascinating and strongly recommended. But if you don’t have 90 minutes here’s a recap of the seven key points the panel made.

1. Not taking attention seriously creates a triple jeopardy

Many marketers know about Double Jeopardy – the effect made famous by the Ehrenberg-Bass institute where brands with lower market share suffer from both lower penetration and lower loyalty.

In this session, Peter Field introduced Triple Jeopardy – three linked threats created when marketers ignore attention as a goal. Attention is important because it builds mental availability, the core of long-term brand building. But three trends are damaging it.

- BUDGET going to the sort of ads that aren’t intended to build attention

- MEDIA PLANNING not valuing platforms that build attention

- CREATIVE WORK that lacks elements that gain broad attention

All three of these threats can be countered. But together they are having a catastrophic impact on effectiveness.

2. The relationship between share of voice and share of market is breaking down

For more than twenty years the “Share Of Voice” rule has served brands well. A close relationship between share of voice and share of market has provided a solid foundation for marketers to set budgets and make plans. Increasing share of voice leads to growth for brands – though the effectiveness of Extra Share Of Voice (ESOV) also depends on creative quality and wise media choices.

Peter Field showed new evidence that this relationship is under serious strain. The correlation between ESOV and brand growth has weakened drastically over the last decade, and even more worryingly the level of “bang for your buck” each unit of investment returns has also collapsed.

Field lays the blame squarely on “the legacy of performance-think” over the last 10-15 years. An emphasis on performance marketing, focusing on short-term sales boosts at the bottom of the marketing funnel, has reduced the budgets (and the impact) of brand-building, top-of-funnel advertising. Performance marketing, ironically, relies on previous attention and mental availability – but it struggles to build that attention itself.

The right choice of media platform and great creative can counteract the decline in effectiveness to some degree – but as the other presentations showed, these too are under threat…

3. Not all share of voice is created equal

Karen Nelson-Field’s talk exposed one of the main issues behind the decline of ESOV as a predictor of growth. As she puts it, “We stopped measuring outward and started measuring inward.” Attention measurement used to be based on human activity; now it’s based on the metadata created by that activity. And metadata simply doesn’t measure some important things.

The most important thing being left out is whether an ad that’s “viewable” is actually being paid attention to. This is something you can only tell by observing human activity, so Nelson-Field has. The results aren’t pretty. On average, less than one fourth of “viewable” time translates into actual attention.

This wouldn’t necessarily be a problem – but the proportion varies dramatically across platforms. The “viewability gap” between time in view and attention isn’t constant, which makes time in view a very unstable metric. The concept of ESOV is based on knowing how much SOV each channel can provide – in other words, how much attention a dollar of spend buys on different platforms. But time in view doesn’t predict attention because digital platforms work so differently.

So you might be getting less SOV than you think. Another reason why the link between ESOV and growth is breaking.

4. Platform choice can limit creative quality

Nelson-Field pointed out another major issue – the vast majority of budget on digital platforms is spent below the attention-memory threshold. Put very crudely, you need to keep someone’s attention for 2.5 seconds before you have a chance of influencing memory. Around 85% of digital ads don’t do this.

That’s bad enough, but it also turns out there are structural issues with some platforms that limit attention even more. Nelson-Field introduced the idea of attention elasticity – the range of attention a platform can deliver. A platform with low attention elasticity has structural limits (driven by its user interface choices) on the level of attention it can generate.

The implications of attention elasticity are serious for marketers. It acts as a limiter – no matter how strong your creative is, the attention it can generate will depend on the platform it appears on. Nelson-Field proved this by measuring attention for the same ads across multiple platforms. In each case the platform’s attention elasticity was the main determinant of attention. For creative quality to make the difference we all know it can, it has to be seen on platforms with high elasticity of attention.

5. The most effective creative elements are in decline

Great creative is suffering from squeezed budgets and attention-killing platforms but as Orlando Wood reminded us all, great creative is still the most effective way to drive the kind of attention that builds strong brands.

Orlando drew on his hit books Lemon and Look Out (published by the IPA) to point out the elements of advertising that are most reliably effective. These are invariably the elements which attract the attention of the right hemisphere of the brain.

The idea of the right- and left-brains doing different things has been rightly discredited, but unfortunately the baby has been thrown out with the bathwater somewhat. The two sides of the brain don’t do different things – they do things differently. And one of the things they do is pay attention to the world differently.

This means different elements in ads capture the attention of the left and right brain. The left-brain approaches the world in a more abstract, task-oriented, focused way, paying attention to parts not wholes and to individual elements not relationships between things. Relationships, distinctive places and times, ambiguities, cultural references and humour tend to appeal more to the right brain.

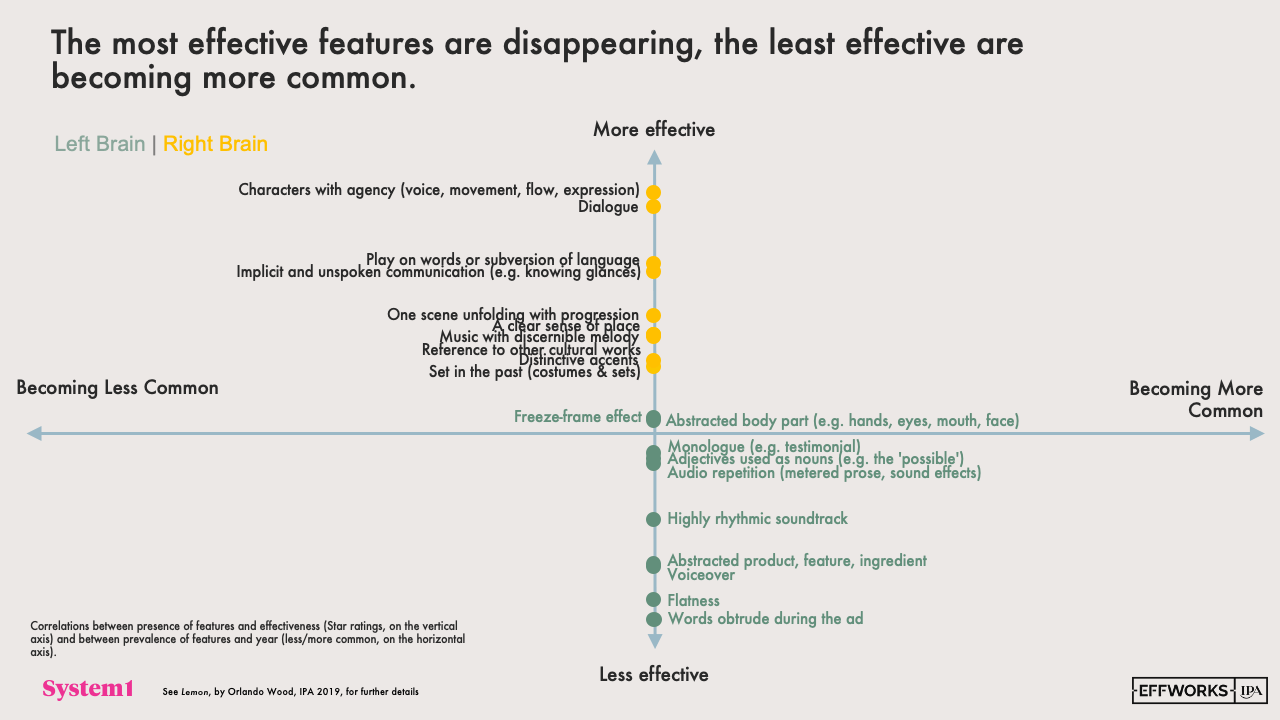

When those right-brain elements appear in advertising they drive greater emotional response and more business effects. But as Orlando’s books describe, these elements are in decline. So are other effective right-brain ones like dialogue, narrative and melodic music. And less effective elements which appeal to the left brain – like highly rhythmic, fast-paced, abstract ads with heavy voiceover and text – are on the rise.

6. Right-brained creative work drives attention too

If you just read the description of left- and right-brained creative work and thought, that sounds like performance-marketing and brand-building ads, then you’re absolutely right.

The two sides of the brain, as Orlando describes in Look Out, pay attention to the world differently. The left brain is the domain of narrow-beam attention – the sense of focus we feel when we are intent on a specific task. The right brain governs broad-beam attention – the wider alertness that lets us notice interesting things or familiar and enjoyable patterns.

Both kinds of attention are useful to marketers. If you’re trying to close a deal with someone who already knows and likes your brand, the narrow-beam attention of the left-brain can be very helpful. But if you want to create that knowledge and liking in the first place, and build your brand by reaching new people, you need broad-beam right-brained attention.

In Look Out, Orlando explores the relationship between right-brained and left-brained elements and attention. It turns out that right-brained elements like human interaction, narrative, and a strong sense of time and location are very effective at capturing attention. Orlando summarises these elements as Character, Incident and Place, and an ad which contains them is much more likely to push audiences over the memory-attention threshold.

7. With economic trouble ahead, attention and brand building get more important

The webinar ended with a pithy summary of how to avoid the Triple Jeopardy.

For salience, sales and lasting effects, it’s brand-building advertising for broad-beam attention in attention-rich media

But might the whole point be moot? With financial storm clouds overhead it looks likely that 2023 will bring a recession. Surely brands should be focusing on performance and not brand-building in that situation?

Absolutely not. In a recession, brand-building advertising gets more important, not less. This may seem counter-intuitive, but think of it this way. In difficult economic circumstances, people have less money to spend right now – they are making cutbacks and looking to reduce spending. Performance marketing – which is all about stimulating an immediate sale – is less efficient in hard times because there’s simply not as much economic activity happening.

Brand-building, though, is more efficient. Disposable income falls in a recession, but brand-building is about securing a share of future spending by building attention. When recessions turn into recoveries, history shows that it’s the brands who don’t “go dark” who recover faster and stronger.

And with economic woes on the horizon, reversing the trends that create the Triple Jeopardy is an even more urgent task.